5 Reasons Why BPG Will Eventually Replace JPEG

There’s a new player in the image compression scene: BPG (Better Portable Graphics), a format based on a single video frame of the new HEVC video codec. BPG was developed by Fabrice Bellard, a very well-known software engineer who also created ffmpeg, a comprehensive and widely used platform for media processing. With no apparent marketing campaign or industry backing, BPG has quickly gained comprehensive media coverage, including articles in Forbes, The Register and DPReview.

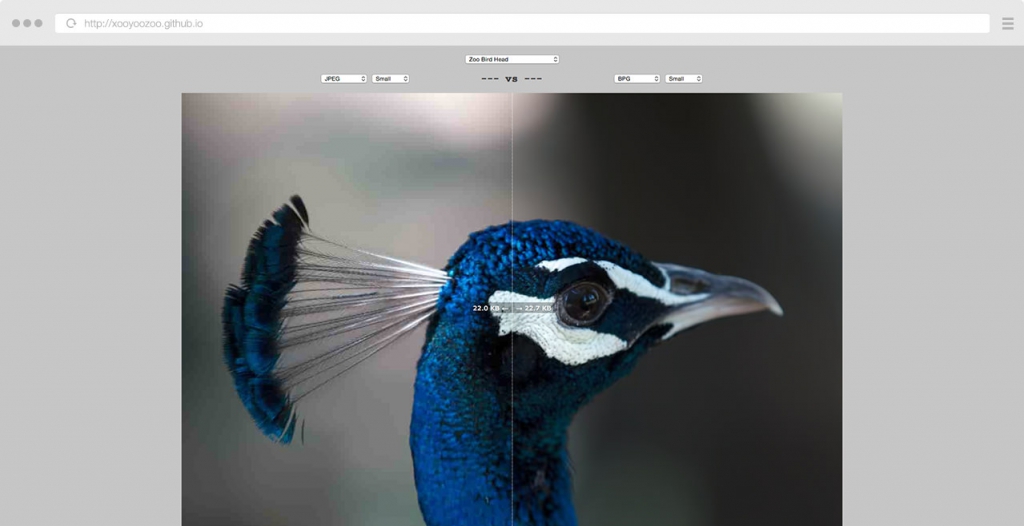

After comparing BPG to other image compression formats using the nice online demo, we’ve downloaded the Windows binaries and played around with them a bit, achieving very nice results in compressing images. Based on these results and on evaluating the technical and market advantages of the new format, we believe that in the long run BPG will be able to replace JPEG as the standard format for image compression, gaining support across the whole value chain from cameras and phones through photo editing software, printing and web publishing. Why do we think BPG will succeed where JPEG-2000, JPEG-XR and WebP have failed? Read below…

BPG is Open Source

The original JPEG standard, and its successors JPEG-2000 and JPEG-XR were developed by international standardization bodies such as ITU and ISO. Developing a technical standard in a committee is a lengthy process, that requires dozens of meetings (each one lasting several days), thousands of “contributions” (technical documents proposing various features of the standard), and takes several years to complete. The original JPEG standards group was formed in 1986, but Part 1 of the standard was approved only 6 years later, in 1992. Then it took two more years to approve Part 2 (Compliance Testing), and 4 more years for Part 3 (Extensions).

BPG on the other hand is an open source implementation that was created in a few months, based on an existing video compression standard (HEVC). As a community-sourced project, there is no need to wait for a standards body to approve or ratify it. Changes can be proposed at any time, and if they benefit the whole community, they are integrated into the main branch. The availability of the source code implementing the standard from day one ensures the wide distribution of software to support the standard across different platforms, and the compatibility of these software implementations with each other. This is in contrast to “the old days” of standardization, where a standard would define the specification only, and then all vendors would implement the spec on their own, and meet again for interoperability testing (also known as “Plug Fests”) to ensure that their implementations are in fact compatible with each other.

One thing to keep in mind is that if a codec is open-source doesn’t mean it is free from IP constraints. There is a patent pool for HEVC managed by MPEG-LA, and there may be additional “essential patent” holders. But that was the situation for H.264 as well, and it didn’t prevent H.264 from becoming the leading video compression standard.

BPG was developed by Fabrice Bellard

Fabrice Bellard, as described in a wonderful profile article by Cameron Laird, is an icon in the open source development community. In addition to developing the ffmpeg media software, he also developed the QEMU hypervisor for hardware virtualization, The Tiny C optimized compiler, a PC-based DVB-T Digital TV transmitter, and many more projects. As a widely respected software engineer, often referred to as a “Super Programmer”, it is only natural that his image compression project will be adopted by the open source community, followed by the industry as a whole.

Previous attempts to replace the JPEG standard were associated with very large companies: The JPEG-XR standard was based on HD Photo technology developed by Microsoft, while the WebP format was developed by Google. In both cases, other major industry players were reluctant to technologies developed by their competitors. The fact that BPG was developed by an individual that is highly respected in the industry, and free from any commercial interests, is sure to increase its chances of market success.

BPG is based on HEVC

BPG is based on HEVC (previously known as H.265), the latest video compression standard that is up to twice as efficient as the previous standard (H.264). In most video compression techniques, there are 3 types of frames: I-frames, which are frames encoded as a whole, independently from other frames; P-frames, which are encoded as differences from previous frames; and B-frames, which are encoded as differences from previous and later frames. BPG is essentially an I-frame of HEVC, with a reduced header to make it even more efficient.

HEVC encodes I-frames more efficiently than JPEG: While in JPEG each 8×8 block in the image is encoded independently, HEVC I-frames utilize redundancy between different blocks, and can encode only the differences between blocks instead of the full block information. It is clear that in uniform areas of the image, where blocks are similar to each other, such encoding (called “Intra Prediction”) can be much more efficient than coding each block independently. This is one of the main contributors to the efficiency of the BPG vs. JPEG. Another important feature of HEVC that is utilized by BPG is CABAC encoding: This is the final entropy encoding of all the HEVC parameters describing an image. CABAC encoding is more efficient that the older Huffman entropy coding used in the JPEG standard.

The fact that BPG is based on HEVC also means that no special hardware needs to be developed to enable quick and power-efficient encoding and decoding of BPG on mobile devices such as phones and tablets. HEVC hardware support is already included in the high-end devices that were released in 2014, and it is expected that more and more devices will include hardware support for HEVC during 2015 and beyond. This creates a huge install base of devices that can efficiently encode and decode BPG in hardware.

BPG is supported now in all main browsers

One of the reasons that BPG will be able to proliferate quickly to many websites is that Fabrice Bellard also implemented the BPG decoder in JavaScript, a language that is suported in all major browsers. This small (56 KB) piece of code can reside on a web page, and quickly download and execute in the browser. This means that in order to support BPG, there is no need to update the version of the browser or install a browser plug-in – just by hosting the small piece of JavaScript on your website, you can put BPG images on your page that any user can view. Many smartphones already support JavaScript in their browser – try browsing to the online demo with your phone to check if it supports BPG playback out of the box.

JPEG is old

The JPEG standard was approved a quarter of a century ago – that’s a very long time in the technology world… During this period, video compression has developed through 5 generations: From MPEG-1 through MPEG-2, MPEG-4, AVC (H.264) to today’s HEVC. So its time to move on, and say goodbye to the JPEG standard that has served us well for a long time.

So what about JPEGmini? Well, you can rest assured that BPG support will not be missing in future versions of our product, and we have already verified in our labs that our optimization algorithm can also do wonders for BPG… But as long as JPEG is still here – you can use JPEGmini today to reduce the file size of your photos by up to 80% with no quality loss.

What do you think about BPG? Let us know in the comments section below.

29 Comments

I seriously doubt that the patent problem can so easily be overlooked, Mozilla for instance will probably wait that the Daala project comes with a real patent free format rather than adopting something potentially patent encumbered (remember what happened with GIF and Unisys and why arithmetic encoded JPEGs are bloody rare).

The format itself has some limitations to keep the compatibility with HEVC: the alpha channel cannot be interleaved with other components, this is a serious drawback since it means that images with transparency cannot be displayed until the file has been entirely downloaded, it also lacks a form of progressive rendering and its chroma subsampling capabilities come straight from a video oriented format (it cannot subsample solely vertically has JPEG does, not often used excepted when you handle some rotated images).

The idea of reusing HEVC is nice but the result is a brillant hack not a modern still image standard.

DivX was also a “brilliant hack” and to this date all DVD players support it… Just because a format did not come from a committee doesn’t mean that is won’t become a [de facto] standard. The opens source nature of the format means that any shortcomings can be fixed relatively quickly in future versions. And regarding the patent issues: They need to be solved anyway to enable HEVC video playback, and HEVC video _is_ a standard that will be supported everywhere. So even if BPG is supported “only” on devices, browsers and apps that support HEVC video plabyack, I think that market is large enough…

Thank you for this write up!! I wasn’t aware of BPG. The linked compatibility page was mind blowing. If you guys are able to improve upon their algorithm like what is shown in jpegmini then I’ll be stunned. Incredible!

Hopefully this is not just another nice idea that never really takes off. We’ve had it with LWF (LuraWave), FIF, JPEG2000 and others. Sorry that I’m not that enthusiastic (yet). The demo is impressive though.

WebP needs client side support. Mozilla, Microsoft and Apple would not implement it. This one can be done on the server side. So I guess it does not matter if the market adopts it or not?

If Adobe doesn’t support it in Photoshop, this will be the first nail in its coffin… How are you converting an image to BPG today?

Sorry I don’t think so. I’ve never heard of BPG. Remember how google’s webp turned out? Not too popular was it? Why would BPG fair any better?

Maybe because it’s not invented by a company that produces a browser? I don’t know, I’m also skeptical but BPG’s advantage over JPEG is more impressive than WebPs. Well, and then there’s this thing called hope…

Thanks by the article!! This will be very nice, waiting for the products update!!

Support via Javascript seems impractical so would have to wait for actual browser support to make an claims of its usefulness.

Currently caniuse.com has no entry for BPG so while the demo was impressive doubtful we will be converting our JPGs anytime soon.

Hopefully the W3C is aware of this an integrates this format eventually into the standard recommendation.

Online demo Bpg shows bright colours squares in dolphin browser on phone. But in chrome on phone it’s ok

Had no fucken idea this existed. Rad

Pretty interesting read. Of course there’s been a few new image types that were going to be “the next big thing” like Google’s WebP.

I also find it funny that the feature image for this article is a png called “bpg.png”. Maybe it’ll be the other way around one day 🙂

I was looking for more solid reasons, like what are genuine performance gains over jpeg? These 5 reasons don’t sound very convincing for me.

I’m ready for BPG – I just hope I never need to send it to a client and have to explain what it is :’)

56KB is *not* small when it comes to mobile payloads. That being said, this seems interesting and I look forward to its development.

None of these is a reason that BPG might win out. Not one. They are geeky reasons that amount to saying “it’s better”, but “better” file formats rarely win.

However, I can say with one word why this might actually win out:

Red.

IMHO there must be a political reason behind companies not supporting better formats (be it image, sound, video etc.). As it is software there is absolutely no sane reason behind software companies, camera/phone/tablet makers, internet sites, OS makers etc. etc. not including native support for better image formats. As it is only a question of writting a piece of code to support that specific file format or implementing an already written piece of code from the maker. I simply do not get it.

Thank you guy!.

I’m interested in this article. I only see the demo website : https://xooyoozoo.github.io/yolo-octo-bugfixes/#camel&jp2=m&png=m

It’s awesome! btw I tried to find the code for this algorithm. but I cannot see in the detail.

Could someone share me the algorithm or code example ( Matlab or high lv language ) thank you in advance 🙂

I doubt BPG will become popular with such a restrictive license and poor performance.

My bet is on FLIF. Best performance both lossless and lossy in terms of quality and size, is progressive, open source and free, no patents.

This was two years ago and in 2017, Jpeg is still king.

It looks like BPG will never pass the experimental phase. There is another format that is slightly supported that uses H.265 technology. Google had it around since 2010. It is called WebP. WebP is not widely supported probably due to the long decompression time to get the image. I mean an image browser is forced to decompress the image and it greatly slows down hardware. That format is best used as a type of lossy ZIP. So convert them to WebP so save on hard drive space and convert them back to JPG for viewing or working with. Yea it does lose a little bit of detail but in HD content it is not noticable.

Amazing informative post. I just heard of BPG! After reading your post, I don’t believe that BPG become popular than JPEG. It is widely used format all part of the world.

i never know about BPG i know something new from your site JPG is most common format we are seeing for images.

Great post and wonderful essentials factor describing here . I have learn lot’s and recommend for any graphic designer for read this content.

Thanks, I really enjoyed the article a lot. Being a 10 years experienced photo editor I always try to prefer jpeg and png format due to it’s over acceptability and easiness to all users. Lovely thinking, cheers!

Incredible post.

This is completely a new learning from me. But still I am concerned whether BPG can replace JPEG in terms of popularity and usages. Very interesting post, big thanks for sharing this one.